The low-lying coastal areas of Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands are under increasing water pressure: From the seaside, storm intensity is increasing whilst sea levels are gradually rising. Sea levels are expected to rise by up to 100 cm by 2100. In mainland areas, more and more freshwater is pushing out of the adjacent catchments and estuaries as a result of flash floods.

In my thesis, I propose to end this conservation and punctually open the dykes to create sediment intake.

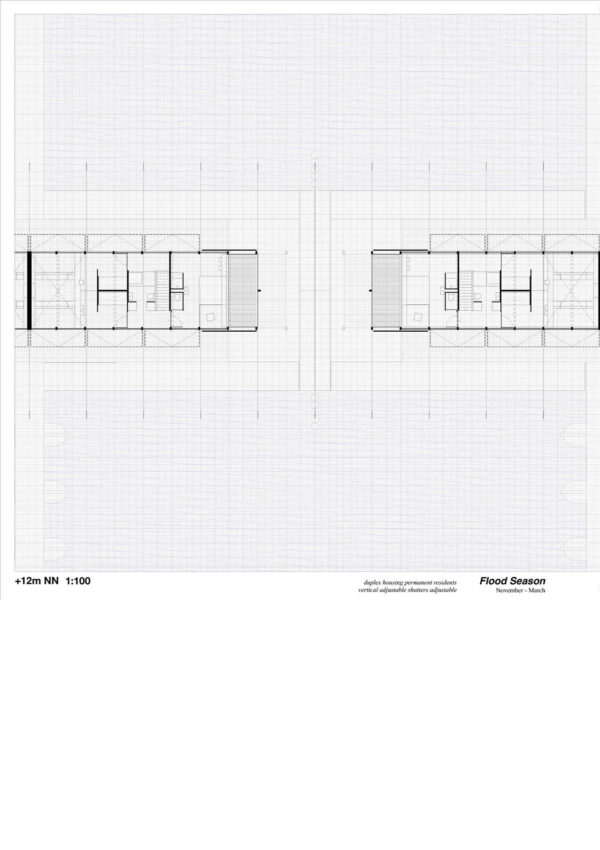

As part of an imagined research project, the dykes in front of Husum, the Capital of Northern Frisia are opened to slough up the land around the buildings by sediment gain and to grow upwards with sea level rise. This upward growth is permitted by the extensive exchange of pigment-rich flood water, mainly in winter. A new intertidal zone develops on the inside of the opened dyke. As cultural structures and protective architectures, the dykes remain effective and preserved. In the event of a storm surge, the opening can be closed, and damage can be prevented. This scenario is situated within the building period until 2100.

A structure is placed 250m behind the opening as device for sediment collection, consisting of elements for coastal protection. It is both a protective infrastructure as well the foundation to a housing development. The shape of its foundations allows the building to conduct water and thus becomes topographically effective.

Analogous to the cultural technique of land reclamation, wood logs are inserted into the soft ground and, during high tide, their geometry affects the flow velocity of the penetrating seawater, resulting in the gradual depositing of material.

Both flood adjusted buildings and re-wetting are not new ideas. However, they have never been conceived together. To this date, it has seemed a paradox to integrate housing developments in such areas as they are usually designated to become nature reserves. Through sediment gain, architecture and ground could join forces to become effective as coastal protection: In selected areas sediment is accumulated – over time a small island would form behind the building. The topography would also serve as a further buffer in case of severe floodings. Deliberate and controlled flooding would also increase the resilience of these areas: In a landscape, which is accustomed to semi-annual flooding, larger surge become less of a risk.

With the project, I aim to convey an alternative perspective on the effects of climate change. Instead of building walls, I would like to question the hard separation of land and sea. At the same time, these changes are not considered as a loss, but as an opportunity to re-establish connection to the land and its many movements; to let oneself be covered in mud to grow upwards.

It shall stay unclear if the building is forming the landscape or if the landscape formed the building. What if, under increasingly extreme climatic conditions, we no longer consider house and landscape separately, but imagine them to move slowly together.

The project was supervised by the chairs of Prof. Tom Emerson and Prof. Milica Topalovic.